It’s the weekend -- time for a book review.

With the dismantling of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the formal dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the world as Americans had known it suddenly changed. America had won the Cold War on its European front from a military and political perspective (largely forgotten at the time was Chinese communism, which had played such a looming role in our two major military conflicts of the Cold War era,) but in some respects the celebration was surprisingly low key.

Some of this, to be sure, was a desire to be magnanimous in victory. Some of it was the result of President Bush the elder promptly involving the U.S. in a series of military conflicts (Panama, Iraq, Somalia) that distracted us. Part of the subdued response, however, was undoubtedly due to the fact that even as the former Soviet bloc was embracing -- as best they knew how -- freedom, capitalism, Christianity, and many traditional Western ideals, here at home things didn’t particularly seem like our principles had won. The inexorable growth of the leviathan state and its attendant ills like the criminalizing of thought (i.e. hate crimes,) were continuing unabated in spite of three consecutive elections of self-proclaimed conservatives to the Presidency. Perhaps most importantly, on the domestic cultural front, leftists who had for decades apologized for or minimized the importance of Soviet communism seemed unfazed by the fact that the grand experiment was over and had indeed crashed and burned, even though its opposition was an often timorous and divided West filled with apologists for socialism and communism.

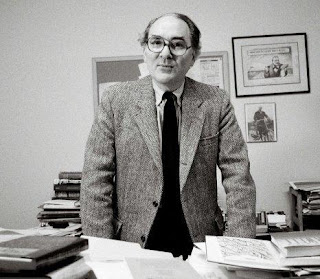

In 1999, with the release of The Twilight of the Intellectuals: Culture and Politics in the Era of the Cold War, Hilton Kramer, by then editor of The New Criterion, provided a collection of essays that he had written from the mid 1970’s to the late 1990’s. Writing in the introduction, Kramer points out:

The Cold War was always as much a war of ideas as it was a contest for military superiority, and it was a war of ideas in which many talented people in the West -- people of intellectual influence and great cultural renown -- fought on the side of the political enemy. That, too, should not be forgotten in the wake of this costly and hard-won victory.

The theme, conveyed indirectly, is that of moral accountability. Accountability should not be confused with recrimination -- the latter is mean-spirited payback while the former is simply a matter of telling the truth. And Hilton Kramer was always for telling the truth.

In any collection of essays, the way in which it is organized tells much, and in the case of Twilight of the Intellectuals, the fact that Kramer leads off with two different essays on Whittaker Chambers sets the tone. By the time most of us today came of political age, the Alger Hiss trials were ancient history. For conservatives, we knew that William F. Buckley, Jr. was close friends with Chambers and deeply respected him, and we would pick up bits and pieces of the story along the way as we read National Review and read Buckley’s books. Many of us, however, didn’t really take the time to know the story and understand its centrality.

Kramer’s essays on Chambers are as heartbreaking as they are chilling. He shows that in the Hiss-Chambers affair, the man who was convicted by two juries of committing perjury regarding his spying for the Soviet Union (the statute of limitations for espionage had passed, so perjury was the best that could be done) was defended and feted by America’s smart set, while the man who told the truth with meticulous attention to detail (Chambers) was vilified and pilloried in the most vicious personal fashion because he had the bad taste to overturn rocks, revealing the Stalinist infiltrators crawling beneath.

One of Kramer’s favorite words in describing the stance of the Cold War liberal-left in America toward the Soviet Union is “mendacity.” It is a wonderful word, one that encompasses not only the incessant lying, but also the fact that there was the perverse belief on the part of liberals that they didn't hurt anyone when defending or minimizing or revising the history of atrocities in the communist world.

The next essay concerns the novelist Josephine Herbst and had intensely personal ramifications for Kramer, since he was (inexplicably, to him) chosen by Herbst to be her literary executor after her death. He had known and spent a significant amount of time with her, and yet it was only after having full access to her papers after her death that Kramer came to learn that Herbst had information that would have substantiated Whittaker Chambers’s central claims, had Herbst only had the courage to step forward and tell what she knew at the Hiss trial. The course of Chambers’s life might have taken a considerably less tragic turn had she done so. Reflecting on the “brutalization” that Stalinism inflicted on the humanity of its defenders, Kramer writes:

It is in the nature of Stalinism for its adherents to make a certain kind of lying -- and not only to others, but first of all to themselves -- a fundamental part of their lives. It is always a mistake to assume that the Stalinists do not know the truth about the political reality they espouse. If they don’t know the truth (or all of it) one day, they know it the next, and it makes absolutely no difference to them politically. For their loyalty is to something other than the truth. And no historical enormity is so great, no personal humiliation or betrayal so extreme, no crime so heinous that it cannot be assimilated into the “ideals” that govern the true Stalinist mind, which is impervious alike to documentary evidence and moral discrimination.

Kramer continues:

The slaughter of the peasants in Stalin’s collectivization campaign, the Moscow trials, the Great Terror and the Hitler-Stalin pact, not to mention a great many later developments... however much [Herbst] may have suffered over them, she nonetheless swallowed them. There was a lot she choked on, but in the end she swallowed it all. Which is why she remained “loyal” in the Hiss case, and in many lesser causes as well. [When she disapproved, it was] always done privately, and never where it would make any difference, and always subsumed under the comforting and exonerating rubric of “What went wrong?”

By beginning with these harsh crudities of Stalinism, the left-leaning reader might breathe a sigh of relief, thinking that no-one on the left actually tries to (or has to) defend it anymore. This is not precisely true, however. Kramer’s essays go on to show how the the anti-war movement of the 1960’s (specifically the phenomenon of fashionable “anti-anti-communism” that came to pervade the academy and journalism,) was very self-consciously involved in the careful rehabilitation of the reputations of Soviet collaborators like Alger Hiss, Josephine Herbst, and Lillian Hellman. (The successful results of such campaigns are amusingly captured in a cocktail party scene in the romantic comedy “You’ve Got Mail,” where Julius and Ethel Rosenberg are the radical-chic topic of conversation.)

By beginning with these harsh crudities of Stalinism, the left-leaning reader might breathe a sigh of relief, thinking that no-one on the left actually tries to (or has to) defend it anymore. This is not precisely true, however. Kramer’s essays go on to show how the the anti-war movement of the 1960’s (specifically the phenomenon of fashionable “anti-anti-communism” that came to pervade the academy and journalism,) was very self-consciously involved in the careful rehabilitation of the reputations of Soviet collaborators like Alger Hiss, Josephine Herbst, and Lillian Hellman. (The successful results of such campaigns are amusingly captured in a cocktail party scene in the romantic comedy “You’ve Got Mail,” where Julius and Ethel Rosenberg are the radical-chic topic of conversation.)

It is with sadness that Kramer, who spent much of his life as a self-described liberal, details the gradual demise of the anti-communist strain of American liberalism over the decades of the Cold War. Kramer devotes an entire section to the topic of “The Strange Fate of Liberal Anti-communism,” writing at length about the magazines The New Republic and Partisan Review. One by one, the remaining intellectual figures of liberal anti-communism were isolated (Sidney Hook,) subjected to revisionism (George Orwell,) stunned by attacks from their left (Lionel Trilling,) or co-opted (Arthur Schlesinger.) There are a couple of particularly illustrative examples from the life of the historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., contrasting his earlier Cold War positions with those he later took. Interestingly, Kramer takes a dim view of the corrupting effect that the atmosphere of the Kennedy White House had on men like Schlesinger -- interesting because modern conservative revisionism often likes to make Kennedy the last of the good Democrats (on the strength of his tax cuts and the Cuban missile crisis,) when it is perhaps more likely that JFK was saved by premature death from being clearly seen -- as something quite different.

Even for those on the left who saw the enormity of Soviet crimes against humanity, it was simply not acceptable to be too critical of the Soviet Union, much less Marxism as a political philosophy. Excuse, minimize, obfuscate... the process continued throughout the Cold War, and then after the Cold War ended, silence, even as monuments to one of the communist “good guys” -- Lenin -- were torn down with gusto across the former Soviet empire. The denizens of those parts knew what leftists in the West were loathe to admit. They knew exactly what role Lenin had played in the creation of a state of terror (including founding the system of concentration camps known as the Gulag.) What Stalin did was not a perversion of Leninism, it was its logical extension.

With essays on Susan Sontag, Sartre, the Bloomsbury group, and many less widely known figures, Kramer details the often unbelievably bizarre world of the intellectual left in the past century. The pages are spiced with wry observations -- for example, Kramer details the fact that the Bloomsbury group lived out their sexually libertine Bohemianism in great physical comfort, being supported financially by well-off parents who symbolized everything they professed to despise about the Victorian remnants of Edwardian British culture. They of course hid their excesses from said parents, lest the gravy train be cut off.

In an essay about the British drama critic, Kenneth Tynan, Kramer likewise notes: “Like so many of the aesthetic rebels of his generation, he had been born into a prosperous middle-class family that provided him with the means of rejecting it.” It is a familiar story to anyone who had the privilege of following in the wake of baby-boomers who were able to live out their own countercultural fantasies only because they had access to bank accounts that had been filled by hard-working bourgeois parents who were living out traditional values (like industriousness, thrift, and probity) that the rebel children despised.

Twilight of the Intellectuals is not a particularly optimistic book. It is telling that unless one had the dates written at the end of each essay, one wouldn’t be able to tell which were written before the fall of communism and which were written afterwards. There is nary a whit of triumphalism in Kramer’s later essays; he of all people knew that the real struggle of the Cold War -- the intellectual one -- had never ended.

In an afterward to the second edition of the book, Kramer concludes:

The fact is, at the very moment in our history when we were most in need of rededicating ourselves to the telling of harsh truths about the crimes perpetrated by our Communist adversaries, our intellectuals were taking happy refuge in the mystifications of deconstruction and kindred attempts to discredit the very idea of historical truth.

It was as if an intellectual Iron Curtain of highly sophisticated mendacity had been erected in anticipation of the fall of the actual Iron Curtain in order to forestall any prospect of a moral reckoning. With the idea of truth reduced to the status of a mere social construct -- and thus dismissible as a malign instrument of power -- history itself had been rendered absurd.

No comments:

Post a Comment