Remind me to pay more attention when my kids tell me about a great book -- might have bought some Lionsgate stock before it skyrocketed in the weeks leading up to the release of “The Hunger Games.” More to the point, I might have read this wonderful little book years sooner. As it was, I finished it a couple of days before the film opened this weekend.

There is something satisfying about a good dystopian book or movie. There is the appeal to one’s grumpy sensibility that yes, indeed, the world really is going to hell in a handbasket. Simultaneously a good dystopian work offers hope: surely things won’t get that bad. At least not while I’m alive. And even if they do, we can fight back.

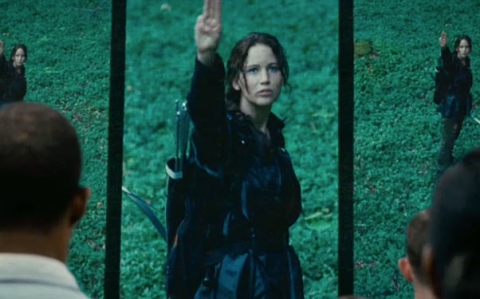

For the 7 people who don’t already know the plot to “Hunger Games,” a post apocalyptic North America is now the nation of Panem (as in panem et circenses -- a conscious reference to Roman gladiatorial spectacles,) ruled by the Capitol, which punishes the outlying 12 districts for their rebellion many years prior by requiring each district to provide one girl and one boy -- age 12-18 -- who are sent to the Capitol where they will receive some minimal training and grooming before putting them in a large outdoor “arena” from which only one will emerge alive. The losers are all dead, but the victor becomes extremely wealthy and privileged, and his or her district benefits as well, which seduces at least some of the subjugated districts into participating enthusiastically by training selected children as skilled killers who then “volunteer” for the games, usually winning.

Much has already been written about author Suzanne Collins’s sources. She drew from the Greek myth of Theseus, was inspired by modern reality TV competitions, and reflects America’s celebrity-obsessed popular culture.

The filmmakers made some interesting visual choices, though, that don’t seem to have been commented on. First, from the novel, we know that the poverty-stricken mining district (District 12) of heroine Katniss Everdeen is what used to be Appalachia. More directly than the book conveys, though, the film depicts a turn of the 20th century poor white place, complete with old black and white photos sitting in tiny house parlors, and with clothes straight out of “The Waltons.” (Music from T-Bone Burnett’s soundtrack gives an effective aural enhancement.) One imagines the privileged Capitol dwellers making condescending jokes about the toothless District 12 folks (see, Bill Maher really would have a job in almost any time-period, as long as he was lucky enough to be born in the right place.) The sharp contrast with what is going on with the smart set in the big city during the 74th annual Hunger Games reminds one of what was once said of the American South prior to the 1950’s -- Reconstruction never really ended.

Economic and political oppression are equal opportunity agents in the Panem era, and again the filmmakers took a brilliant liberty with the book, which never identifies anyone’s race, by making the Rue, the girl “tribute" from District 11 that Katniss allies with in the arena, black. Also black are Thresh, the boy tribute counterpart from District 11, as well as nearly all of the folks watching them back home in this agricultural district that feeds the Capitol (imagined by the author as being in what is now Georgia,) but is itself left to go hungry. A scene shows District 11 rioting after Rue is killed in the arena in spite of Katniss’s attempt to save her -- it is a moving scene, complete with dogs and water cannons and riot police, visually referencing the powerful images of violent civil rights clashes in the American South that we’ve all seen in old news footage.

As a book, The Hunger Games is a spare work. It’s effectiveness comes in no small part from not getting bogged down in futuristic details. Collins used its setting in the distant future to maximum advantage, allowing her a blank slate when she wanted it. The only political, cultural, and scientific information that is conveyed is that which is necessary to the development of the characters and the plot. The central question of how to live as a human in an inhuman setting is left front and center without distraction.

That said, it was a bit odd to look around the packed theater, realizing that while a theme of the book is the horror of children being forced to kill each other for the entertainment of viewer, here we all were, looking forward to being entertained by a film about children being forced to kill each other. Life imitates art, which imitates life.

Film adaptations of novels, as was discussed in the MH review of “John Carter,” often either take unnecessary liberties with the story or conversely sometimes follow it slavishly in a way that just doesn’t work on the screen. Taking inventory after watching the film, it is impressive to note that what the movie changes or adds are overwhelmingly things that just wouldn’t translate well to the screen, and no more. It is an impressive adaptation on that score, and deserves all of the hoopla that currently surrounds it.

A final note: the only other geographical reference that is mentioned in the novel is that the Capitol is in what was once known as the Rocky Mountains. It was the Capitol’s location in the Rockies that gave it a natural barrier that made it hard for the rebelling districts to conquer it in the civil war some 75 years prior. Capitol life is just as deliciously garish as one imagined it when reading the book -- in yet another brilliant visual choice, there really aren’t any costumes in the Capitol that haven’t basically been seen in New York or Paris fashion shows of the last 30 years. The loony look is in sharp contrast, to Montana eyes, with the clean beauty of the towering mountains that surround the futuristic city.

Watching these scenes from “Hunger Games,” it was hard not to muse: “yup, knew it, knew it, knew it... never should have let those crazy Californians move here...”

No comments:

Post a Comment